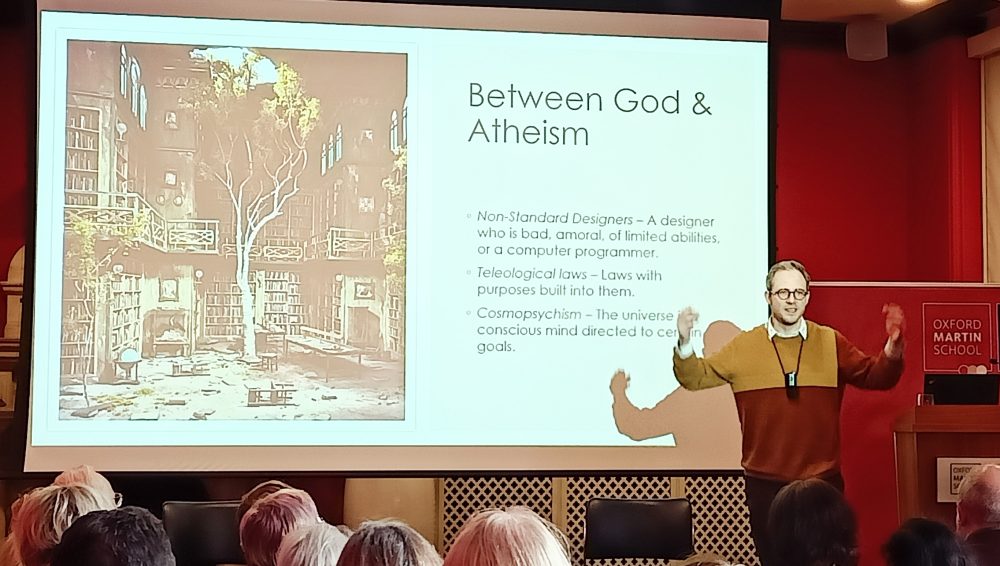

One of those insides: the Oxford Literary Festival 2024, where Philip Goff had also come for war. As the Goths disrupted the Pax Romana, or as Philip of Macedon marshalled against the Achaemenids, so are his chosen minefields of debate: panpsychism and teleology, two contentious topics.

How contentious? Take Mind and Cosmos released by the atheist philosopher Thomas Nagel in 2012. A sort of army of anti-teleological sceptics emerged to contain the Nagelite temerity’s ‘head above the parapet’. The heresy? Claiming that purpose or directedness (teleology) was innate to the inner most structure of the physical world, not a mere addendum.

Or take, in 2006, the philosopher Galen Strawson openly arguing for panpsychism – a ‘mind fundamentally everywhere and in ‘everything’’ position – against the mainstream ‘physicalist’ view. Physicalism was incoherent, said Strawson, because it claimed that consciousness (something able to experience itself, however simply) had emerged from a physical reality that was ‘non-conscious’ and ‘non-experiencing’. There was no ‘like to like’ aspect.

This chasm was so vast – and tortured in speculation and circular reasoning – that the parsimonious answer was to see some form of basic experience or consciousness as innate and fundamental to this underlying physical reality. From philosophic and scientific quarters there was a befuddled sense that Strawson had crossed some sort of red line.

Yet the panpyschists have not retreated. The ‘Nagelites’ have pressed on. A new set of teleological possibilians now push their wedge into the field. Philip the Goff is the cutting edge of a Māori-like ‘warrior of telos’ intent of outlawing an easy to get away with soft nihilism.